"Ex Cathedra" refers to the Pope’s rare and authoritative pronouncements on faith and morals, believed to carry divine protection from error. Rooted in the Catholic understanding of papal infallibility, it’s a concept that often puzzles Protestants and highlights the unique role of the Pope in the Church.

“Ex cathedra” is Latin for “from the chair,” referring to the Pope speaking with supreme authority. It’s tied to his role as successor to St. Peter. Catholics believe these statements are infallible on matters of faith and morals.

The Pope speaks ex cathedra only when he defines a doctrine explicitly, intending it to bind the whole Church. This happens rarely, under strict conditions set by Vatican I in 1870. It’s not a casual opinion but a solemn act of teaching.

One clear example is Pope Pius XII’s 1950 declaration of the Assumption of Mary—that she was taken body and soul into heaven. It met the criteria: a definitive teaching on faith, proclaimed to all Catholics. Such instances are exceptionally rare in Church history.

Catholics believe Jesus promised to guide the Church through Peter and his successors (Matthew 16:18). Ex cathedra statements are seen as protected by the Holy Spirit from error. This applies only to faith and morals, not personal views or other topics.

Ex cathedra pronouncements are extremely rare—only a handful are widely recognized in 2,000 years. The Immaculate Conception (1854) and the Assumption (1950) are the most cited modern examples. It’s not a frequent tool but a last resort for clarity. Popes prefer councils or ordinary teaching instead.

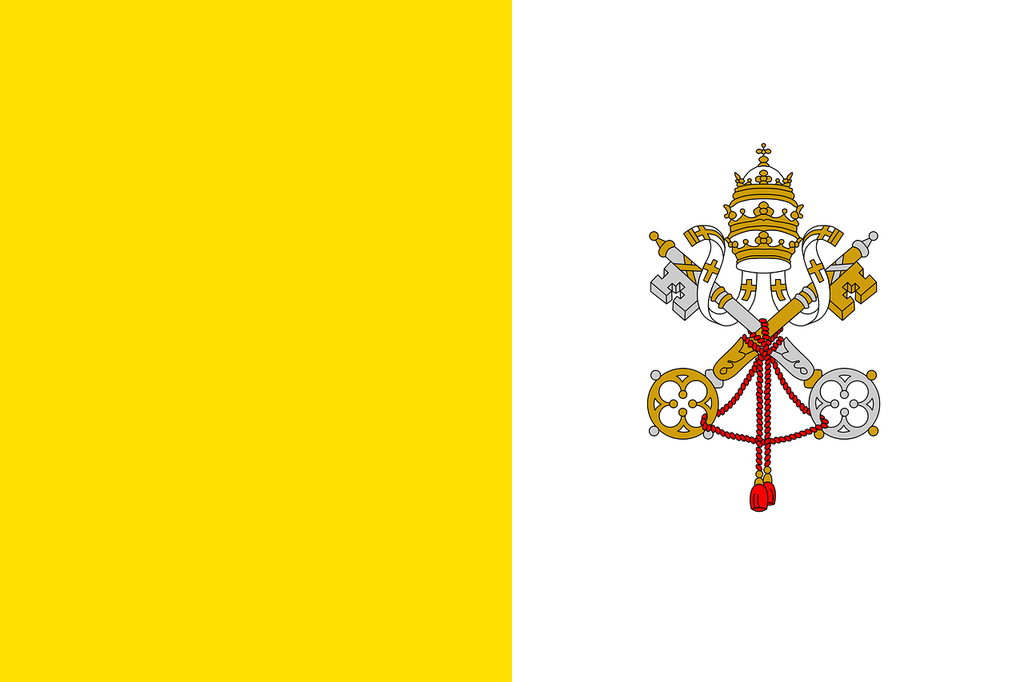

The basis lies in Scripture, like Matthew 16:19, where Jesus gives Peter the “keys of the kingdom,” implying binding authority. Tradition supports this, viewing the Pope as Peter’s heir. Vatican I formalized it, arguing the Church needs a final voice. Protestants often dispute this, favoring Scripture alone.

Most papal statements, like speeches or encyclicals, aren’t ex cathedra and don’t claim infallibility. Ex cathedra requires a clear intent to define doctrine universally. It’s a higher bar, reserved for settling major disputes or affirming core beliefs. Regular teachings guide but don’t carry the same weight.

Protestants often reject ex cathedra authority, arguing it lacks clear biblical backing beyond Peter’s initial role. They embrace “sola scriptura,” seeing Scripture as the only infallible guide. The idea of a human leader claiming divine protection feels like overreach to them. It’s a key divide from the Reformation onward.

The concept grew over centuries, rooted in early Church councils and papal leadership, but wasn’t fully defined until Vatican I in 1870. That council, amid political upheaval, clarified infallibility to strengthen the Pope’s role. It built on prior Tradition, like Pius IX’s Immaculate Conception decree. Critics say it was a power grab, but Catholics see it as continuity.

Ex cathedra matters because it offers Catholics certainty on essential beliefs in a skeptical age. It’s a rare tool, showing the Pope’s role as a unifier and guardian of truth. For dialogue with Protestants, it’s a sticking point—highlighting different views on authority. Its scarcity keeps it impactful when used.